Today, I’m diving into another exciting project: creating a Frankenstein Amiga from various parts I have lying around. Most of these parts come from a job lot of leftover spares I found on eBay. You might be wondering why I’m doing this. Well, I’m challenging myself and also building an Amiga for a charity auction organized by a friendly man named Lee from the YouTube channel More Fun Making It.

The Challenge Begins

There’s something a little strange going on with this Amiga 500 Revision 5. It seems that not all the RAM chips are managing to output TTL logic levels. Based on what I’m seeing on the scope diagram, it’s giving me random green and blue flashes. So, I’m going to pull all the RAM out and socket it. Having the RAM in sockets will be a much better solution for the new owner, especially if any of the RAM I’m installing goes bad in the future.

A Series of Unfortunate Events

The first thing I desolder, ignoring my marks, is the resistor pack. Well, let’s just style that out and pretend no one noticed (lol). Now, all the RAM has been removed, before we can solder in any of the new sockets for the RAM, we need to tack back in those resistor packs—the ones I unsoldered for no reason. Not that I’m planning to put any of the original RAM back in, but let’s go ahead and test it to see if it shows up as bad. Amazingly, all of the RAM tests good. I suppose the heat from desoldering the chips might have revived it, or maybe the logic levels I saw are enough for the tester but not for the Amiga. Or perhaps the RAM isn’t the issue, and we’ve got something else causing the Amiga not to function.

Progress

Time to start putting the sockets in: 16 * 16 pin DIP sockets, that’s 256 solder points plus the resistor packs that I unsoldered for no reason. I tack in one socket and solder it up to make sure I’m happy with the temperatures before I go ahead and install all the rest. I tacked in the rest using the two voltage pins, 5 volts and ground. The followed up by soldering the rest of the pins and clean up the flux. That’s all the sockets installed. Now they just need chips.

Installing the RAM

I remembered someone saying they hated turn pin sockets because they’re hard to line up with the chip pins. So I thought I’d showcase how I do it. This is just how I do it; it’s not advice. I’m not a chip insertion instructor. If you don’t like it, don’t do it. I’m just saying it works for me. Basically I insert one row of pins and then gently apply pressure to the other side while running my tweezers across the chip pins this locates the pins in the socket, it usually takes a couple of strokes for all the pins to align then the chip just goes in without issue. This is similar mechanics to picking a lock…

All the RAM is installed and looking lovely. I took the liberty of fixing the ROM socket so it will take a 27C400 EPROM or a later mask ROM. This is another future-proofing step for the next owner should they want to upgrade to a later Kickstart version.

Final Touches

We have life! I’ve cleaned up the flux and covered the bodge wires from the ROM socket modification. We have a working board, but we need more than that to build a full Amiga. In the same job lot of parts, I have several bits of keyboards. This is where it gets even more Frankenstein. The keys aren’t laid out in the same way as my other 500s. I think this is from an earlier keyboard. The controller is from a Rev 6 Green Power Light. If you can properly identify the original revision any of these parts came from, then please comment on the video.

Testing and Tuning

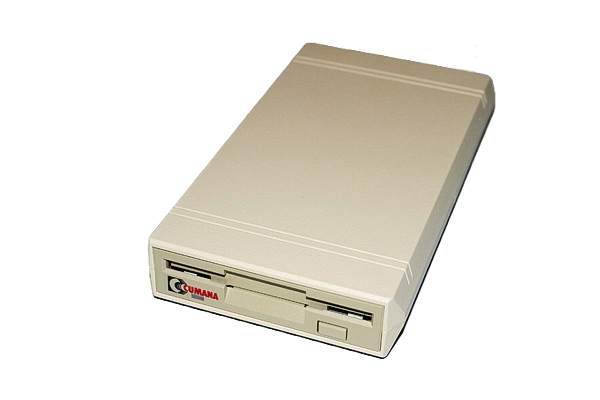

Hooking it all back up with the keyboard and making sure it’s happy before we swap out DiagROM for Kickstart and try booting the Amiga into Test Kit. After confirming all is well with the Amiga, the next step is to get it to boot into Workbench and see if we can load StarTracker from the external GoTek drive. The plan is to load a module and play it, which will give I/O, graphics, and RAM a fairly good workout.

Going the Extra Mile

Since we’ve opened Pandora’s box, I thourght why not see if we can get that 512K of RAM in the trapdoor to be chip RAM? Having a total of 1MB chip RAM opens more games and options for the next owner. We just need an 8372A Agnus some little modifications. JP2 needs to be swapped, we need to cut a trace from Gary to the trapdoor, and we need to cover pin 41 on Agnus to keep it in PAL and prevent it from switching to NTSC.

While you weren’t looking, I’ve sprinkled a little cosmetic customisation over this Amiga 500. All we need now is a case.

Part 2 coming soon!

Building this Frankenstein Amiga has been a labor of love, filled with moments of frustration and triumph. I hope it finds a good home at the charity auction and brings joy to its new owner!